The “Law on the Formation of a New Berlin City Community” came into force on the 1st October 1920, triggering a long-standing dispute over the political responsibility for the expansion of Berlin. The social problems of the densely populated city of Berlin and the prosperity of the surrounding cities and municipalities should be balanced by incorporation into a single large community.

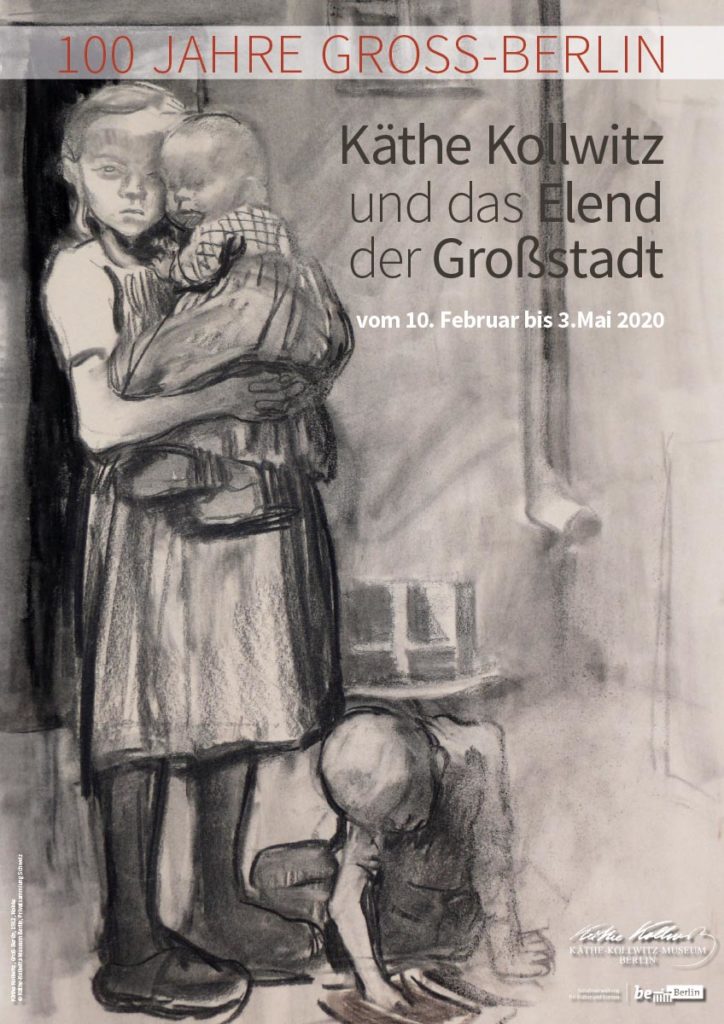

Grievances caused by cramped living conditions, unemployment and life prospects have been a topic in the visual arts since the 1910s. In addition to Hans Baluschek and Heinrich Zille, Käthe Kollwitz in particular was considered a committed artist who knew how to portray social misery with empathy in a forceful visual language. Socially committed motifs, which she mostly created on commission, can be found throughout her work. In 1906 and 1925, for example, she dedicated herself to the misery of women who worked in the home. In 1908-09 she created a series of ‘Pictures of Misery’ for the magazine Simplicissimus in which she addressed unwanted pregnancies as well as alcoholism and violence.

As early as 1912, she designed a poster to support the formation of a Greater Berlin community in order to draw attention to the continuing grievances after its creation, especially in the economically difficult years after Germany lost the First World War.

In 1920, on behalf of the State Commissioner for National Nutrition, she directed her attention to the poor nutritional situation in the city and the resulting diseases by designing posters against the consumption of alcohol (1922) and for the abolition of paragraph 218, which outlawed abortion (1928). The food situation of the poorer population dramatically deteriorated as a result of hyperinflation. Käthe Kollwitz joined the women’s initiative to create soup kitchens, which was financed by “nutrition money”, which Kollwitz advertised on posters in 1924.

Independent of these commissioned works, Kollwitz created several graphic pamphlets in the mid-1920s, in which she took up themes of these posters and processed them artistically. The cycle “Proletariat” (1924/25) was among these pamphlets, as were the works “Städtisches Obdach” [Municipal Shelter] from 1926 or “Das Letzte” [The Last One] (1924). But she also worked intensively on the drawings that stood under the motto “I want to have an effect in this time”.

In its exhibition, the Berlin Kollwitz Museum is therefore showing many drawings that bear witness to the artist’s struggle for quality and heightened expression.

Thanks to generous loans from an important private collection in North Rhine-Westphalia and a Collection from Switzerland, it is possible to compare drawings and prints side by side. The great skill of the artist is as evident as her compassionate commitment.

The exhibition shows about 30 rarely shown drawings and graphics, mostly from the 1920s.